I’m starting a new section on my blog and YouTube channel bringing you some cool cardiology related topics that you might not have heard about. To kick things off I wanted to talk about Lyme disease- and more specifically a possible complication of Lyme disease known as Lyme carditis. And if you prefer videos to reading check out my YouTube video on the topic and be sure to give it a like and subscribe!

Background: what is Lyme Disease?

Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi (and rarely Borrelia mayonii). It is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected tick, as depicted below.

Why is it called Lyme Disease?

Lyme disease got it’s name from the small coastal town in Connecticut back in 1977 when Yale researchers identified clusters of what they initially called Lyme arthritis but then changed the name 2 years later to Lyme disease (1).

What are typical symptoms?

Classic Lyme disease typically causes a ‘bullseye-like rash’ on the skin on average 7 days after the initial tick bite but can happen anywhere between 3-30 days after the initial tick bite known. The medical term for this is erythema migrans. Erythema migrans can manifest differently, as below (2). It is rarely itchy or painful and can have a variable appearance. Additionally in dark skinned individuals it can be difficult to appreciate or visualize well.

Other symptoms that can happen anywhere from days to months after the initial tick bite include headache, neck stiffness, and severe joint pain and swelling that normally involve the knees and other large joints. So why is a cardiology fellow talkign about Lyme disease? Because a potentially serious and life threatening complication of Lyme disease is Lyme carditis.

What is Lyme carditis?

Lyme carditis occurs when the bacterium infects the heart tissue and disrupts the normal electrical conduction system of the heart. This can have a variable clinical expression. The most serious complication is complete heart block.

What is complete heart block?

To understand the complete heart block let’s look at what normal conduction of the heart looks like. To create a coordinated heart beat your heart conducts electrical impulses down a network of nerves. It goes from the SA (sino-atrial) node to the AV (atrio-ventricualar) node, then down to both ventricles, as below.

In complete heart block the top and bottom chambers of the heart are unable to communicate with one another and beat independently. This is also why complete heart block is also referred to as third degree AV block because the electrical impulses are unable to get through the AV node.

Why is complete heart block a big?

Normally the top chamber of the heart is in charge. It sends impulses down the electrical system of the heart and the ventricle does as its told. So what happens when the ventricle never receives any of those electrical signals? Your heart has a backup system for these very instances but it is far from perfect. This back-up system is normally inhibited by electrical impulses received from the SA or AV node but when it never receives those impulses it generates a ventricular rate of about 20-40 beats per minute. This means that you might only be able to sustain a heart rate of about 20-40 beats per minute! Additionally this back-up system isn’t always 100% and in Lyme carditis can lead to a fatal arrhythmia. It is serious and should be treated in the hospital.

What are the symptoms of complete heart block?

A slow heart rate also explains symptoms of complete heart block. Think about what happens everyday of your life when you stand up to walk around- your heart beats faster. If your heart can’t increase the rate that your ventricle beats then your brain is not going to get enough blood and you will feel faint, lightheaded, dizzy, and could even pass out. Passing out, or syncope, is your body’s way of making the heart not have to work against gravity but can also seriously hurt you or somebody else depending on how you fall. Other symptoms of complete heart block can include symptoms severe shortness of breath, palpitations, or chest pain.

How do we treat Lyme carditis?

The first thing we do is treat empirically for Lyme disease with antibiotics. The confirmatory lab tests can take a while to get back and some people don’t develop antibodies until a few weeks after infection. So we don’t waste any time and start treating as the benefit fo treatment often far outweigh the risk of the antibiotics. In the hospital we typically use Ceftriaxone and then switch to oral Doxycycline for a typical duration of about 21 days.

Not everyone who develops Lyme carditis develops complete heart block. There are varying degrees of heart block. About 4-10% of patients with Lyme disease develop some form of Lyme carditis (3). Out of the 4-10% of patients who develop Lyme carditis, about 90% of those only develop 1st degree atrioventricular block (AVB). 1st degree AVB is a benign form of AV block and can often be seen in normal otherwise healthy patients in the general population. However patients who develop new 1st degree AVB in the setting of Lyme disease infection should be watched in the hospital on continuous cardiac telemetry monitoring because it is a good predictor of those who might develop complete heart block.

If you develop hemodynamically significant heart block we often use a temporary pacemaker to ensure that your heart rate is adequate. We place place these through the jugular vein and depending on the type of temporary pacemaker that your receive are either floated to sit in the right ventricle or are screwed into the heart to ensure adequate electrical transmission. Depending on the type, temporary pacemakers are only able to stay in place between 2-7 days and are not a permanent solution.

The good news is that most people who develop complete heart block due to Lyme carditis fully recover with antibiotics and do not require a permanent pacemaker.

How do you prevent Lyme disease and where is it found?

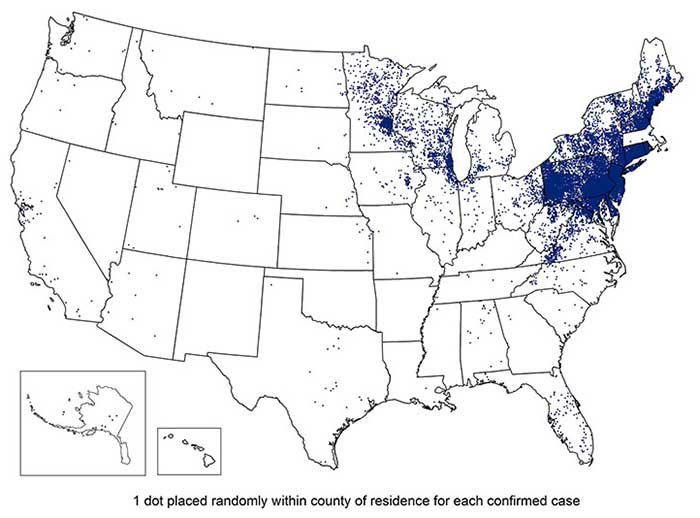

The last teaching point I’ll make for is the importance of checking for ticks after you leave a heavily wooded area. Lyme disease is endemic to the northeast, north-central, and mid-Atlantic regions of the US but can be found elsewhere, as below.

How do you remove a tick safely?

Now let’s say you notice a tick attached to you. What do you do? Try to get a small tweezers if you can and grasp it from as close to your skin surface as you can, as below.

Unfortunately if you just grab it from the body you can potentially rip off the body and leave its mouth stuck on you. The goal is to get the tick off you ASAP! So don’t use remedies like paints, nail polish, or petroleum jelly to wait for it to fall off. After you remove the tick you can flush it down the toilet, kill it in alcohol, or drop it in a sealed bag.

Then call your doctor

Questions we will ask will attempt to narrow the timeline of when the tick attached to you. Interestingly it takes about 36 hours being attached to you for the tick to transmit the bacterium to you. The reason for this is that the bacteria lives inside the tick gut and it takes about 36 hours for the tick to get so engorged on your blood that it actually vomits and in doing so transmits the bacteria before detaching and falling off.

So technically if you went hiking and noticed a tick one hour later then you might not need any treatment for Lyme disease. The reason why it’s important to call your doctor is that a prophylactic treatment for Lyme disease is a single dose of oral doxycycline which typically outweigh the risks of possible contracting and developing complications of Lyme disease.

Works Cited

- Delaware, T. (2020). Lyme Disease Information – Delaware Health and Social Services – State of Delaware. Retrieved 28 July 2020, from https://www.dhss.delaware.gov/dhss/dph/epi/lyme.html#:~:text=Lyme%20disease%20gets%20its%20name,the%20attention%20of%20Yale%20researchers

- Lyme disease rashes and look-alikes | CDC. (2020). Retrieved 28 July 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs_symptoms/rashes.html

- Scheffold N, Herkommer B, Kandolf R, May AE. Lyme carditis–diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(12):202-208. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2015.0202

I hope you guys enjoyed this post. If you liked this post drop a comment below and subscribe so you don’t miss my next post or drop a comment below if there’s something cardiology related that you think would make a cool post or YouTube video and I’ll see if I can make one for yah.